The Jacobite cause, and what can be argued to be a major political movement within the British isles that lasted decades, was propelled by the belief in the reinstatement of the Stuart lineage on the English throne. The Glorious Revolution of 1688 in England ousted the Catholic King James II and replaced by him with his Protestant daughter, Mary II, and her husband, William III of the Netherlands. After the revolution, supporters emerged of the original Stuart lineage, who were both religious and political, and sought to restore a Stuart king on the throne. The Jacobite movement lasted for 60 years and had a total of five organized attempts to overthrow the Hanoverian monarchy which included two generations of Stuarts, Prince James Francis Edward Stuart and his son, Prince Charles Edward Stuart. The final attempt to overthrow the crown ended in defeat in 1745-46, with an infamous battle known as “The Forty-Five Rebellion.”

Support for the Jacobite cause was widespread throughout the British isles, with Jacobites in Scotland, Wales, and Ireland and becoming prominent after 1688. Reasoning for support varied based on religious ideology in areas like Scotland and Ireland, who were largely Catholic, to political reasonings for the conservative Tories in England. There were numerous insurrections and rebellions, with few standing out due to their infamous nature in the historical records of the Jacobite cause. The “Fifteen Rebellion,” of 1715, led with support by the Scottish Jacobites for James Francis Edward Stuart, failed. The most widely known attempt is that of “The Forty-Five Rebellion,” in 1745, where Prince Charles Edward Stuart, son of James Francis Edward Stuart, with largely the support of Scottish forces, attempted a coup. The final battle at Culloden, after success in Prestonpans and Falkirk in previous months, ended in stinging and final defeat for the Jacobites.

Historians have long debated the prevalence of the Jacobite cause in Scotland and the effect of the cause on Britain. Continuous controversy has sparked between historians over the potential positive and negative ramifications socially, politically, and economically on the 17th and 18th centuries. Economic historians John Wells and Douglas Wills argue that, “The source of this (economic) threat was the deposed monarch, James II, and later his son James III, who never renounced their claim to the English throne. With their supporters within Britain–known as the Jacobites–and the active support of France, the deposed Stuarts spend the rest of their lives trying to regain the English crown.” Wells and Wills purport that the Stuart cause threatened the “development of post revolutionary Britain.” The Jacobites caused instability within the realm due to the possibility of an “alternative regime,” which they propose then continuously produced economic instability throughout the decades of rebellious activity.

In contrast, other historians argue that the Jacobite movement was more of a political movement than a cause for a singular monarchy to overthrow another and cultivated nationalism in places like Scotland and Ireland who were actively seeking home rule. In Scotland, historian Allan I. MacInnes argues that Jacobitism allowed for “patriotic identification with Scotland” as well as a “political culture of Scottish Jacobitism” which was “sustained in terms of its confessional and intellectual development, its organizational structure and its commercial and social networking.” Jacobitism had positive effects on establishing a Scottish national identity in those that supported the Jacobites as well as a way for those who didn’t as anti-Jacobites. MacInnes suggests that Jacobitism as a cause, in the years in which rebellions were actively attempting to establish a Stuart king, eventually turned into a total political movement. A newly emerging political culture sustained itself in Scotland after 1745 through political debates, dialogue, and more politically focused scholarship and thinking.

It is apparent that the Jacobite cause had a direct effect on multiple aspects of social, economic, and political life across Great Britain from 1688-1745. The Jacobite cause took hold more rapidly in Scotland, but also had supporters in England, Ireland and Wales. There was also a a broader European element, in which the Stuart pretenders (old and young) saw support from other Catholic monarchies such as Spain and France. These European countries sought to depose the Protestant monarchs in England and reestablish Catholic supremacy across Europe, both on the continent and in Great Britain. Jacobitism became an impetus behind the ability to turn back the clock on the Protestant reforms that had swept across Europe centuries earlier. With relations between France and England increasingly deteriorating, France saw an opportunity with the Jacobites.

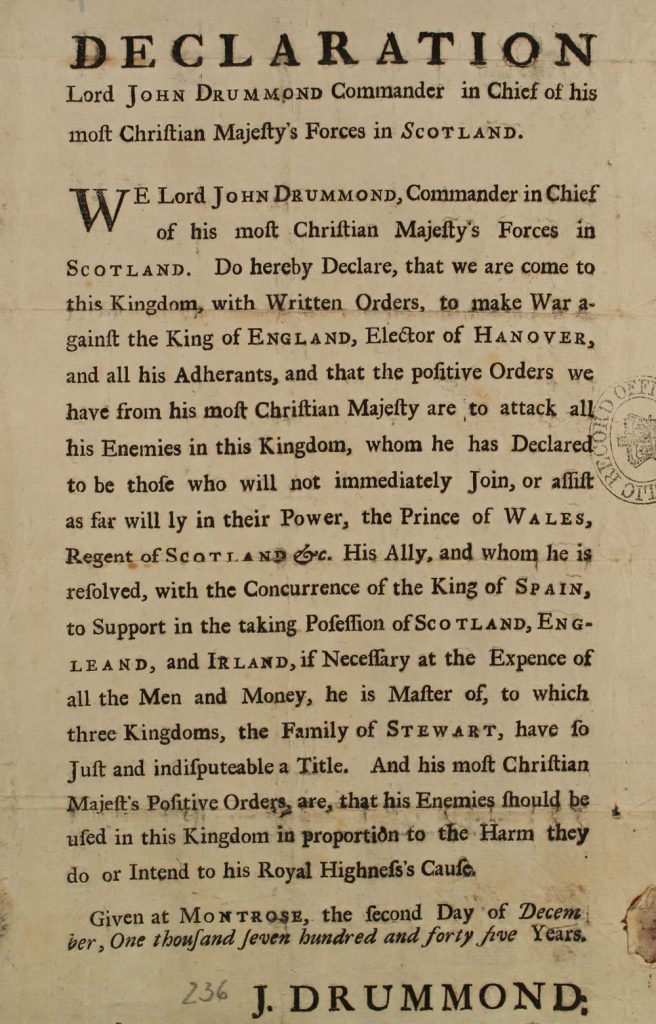

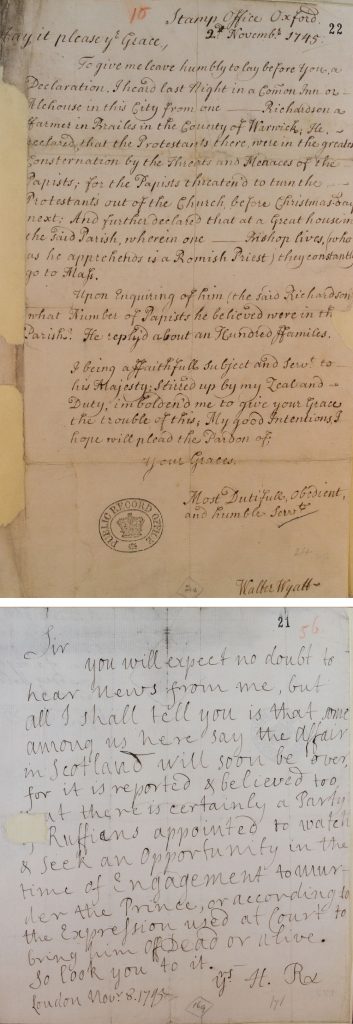

The English saw the Jacobites as a Catholic threat to the Protestant supremacy that was established in the 16th century. In a letter written in 1745, an Englishman wrote about “papists” who “threatened to turn the Protestants out of the Church.” Many Jacobite supporters were Catholic, as was Prince Charles and saw their call to the cause for religious purposes. In December 1745, Prince Charles’ Scottish forces declared war on those who opposed them, with support from Spain. Jacobites in Scotland were committed to assisting in the establishment of a Catholic monarch and received support from Spain in their crusade. Lord John Drummond wrote, “His ally, and whom he is resolved, with the concurrence of the King of Spain, to support in the taking possession of Scotland, England, and Ireland, if necessary at the expense of all the men and money, he is master of, to which three kingdoms, the family of Stewart [sic], have so just and indisputable a title.”